Fire Threatens Rare Forests in Argentina

Jan. 12th, 2026 05:01 amSummer is usually peak tourism season in Argentina’s Chubut province, a time when hikers and sightseers arrive to explore glacial lakes and cirques, alpine valleys, and towering forests. In January 2026, however, some visitors to the remote Patagonian region instead found themselves fleeing raging wildland fires.

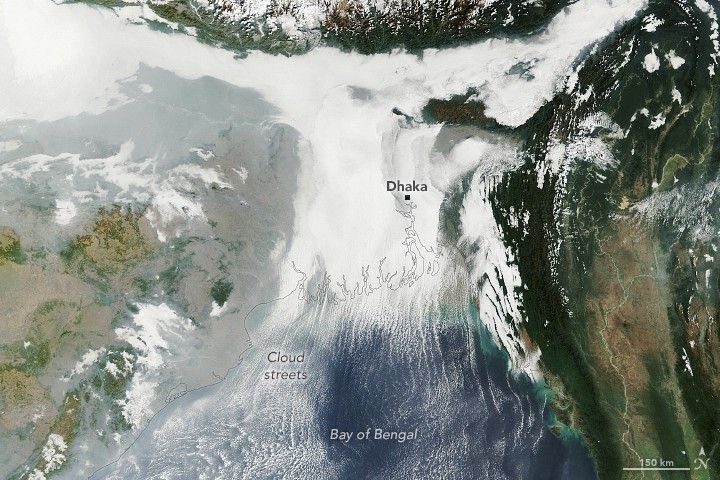

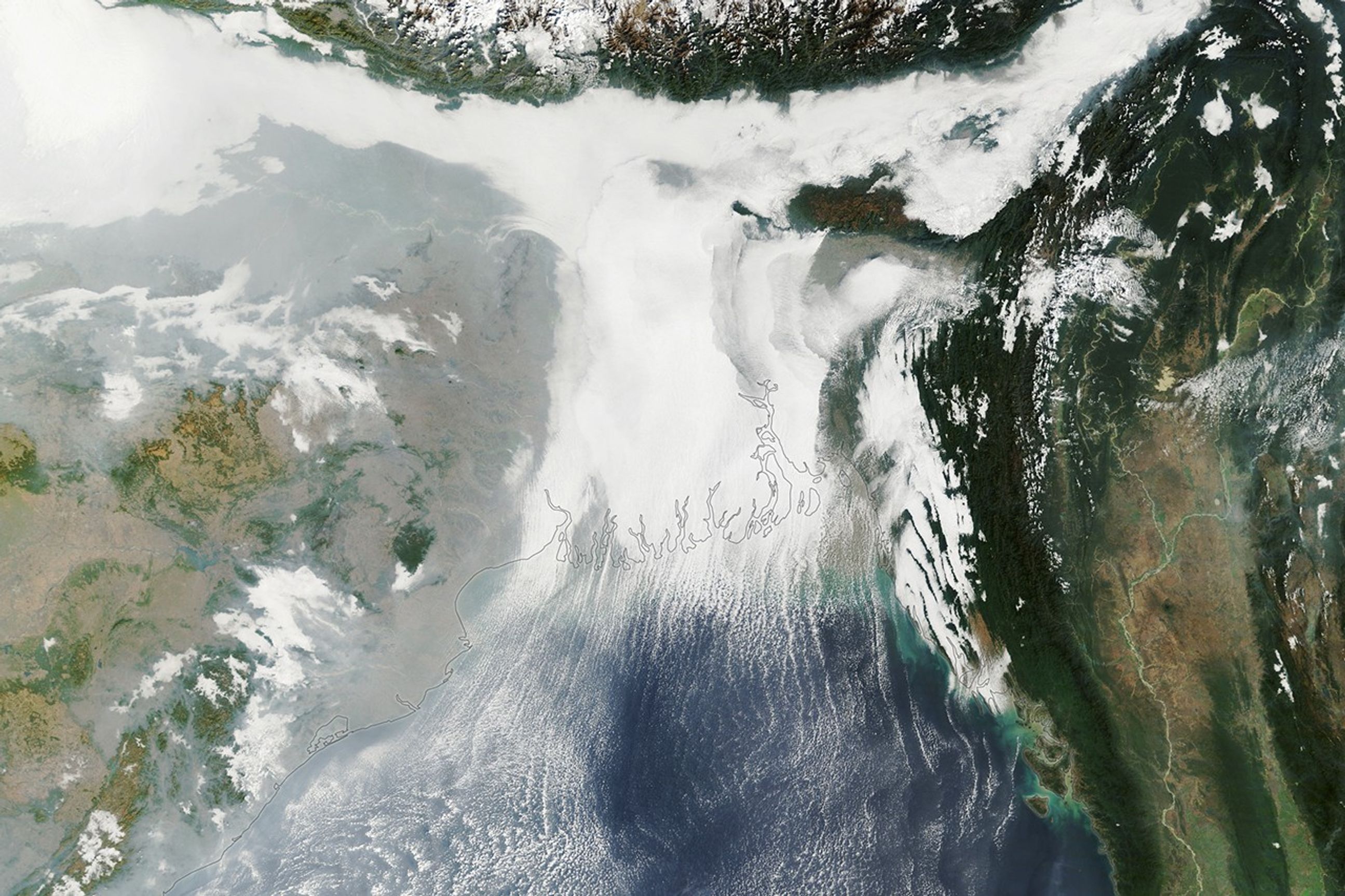

On January 8, 2026, the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured this image of smoke billowing from two large fires burning in and around Los Alerces National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site. NASA satellites began detecting widespread fire activity in the area on January 6.

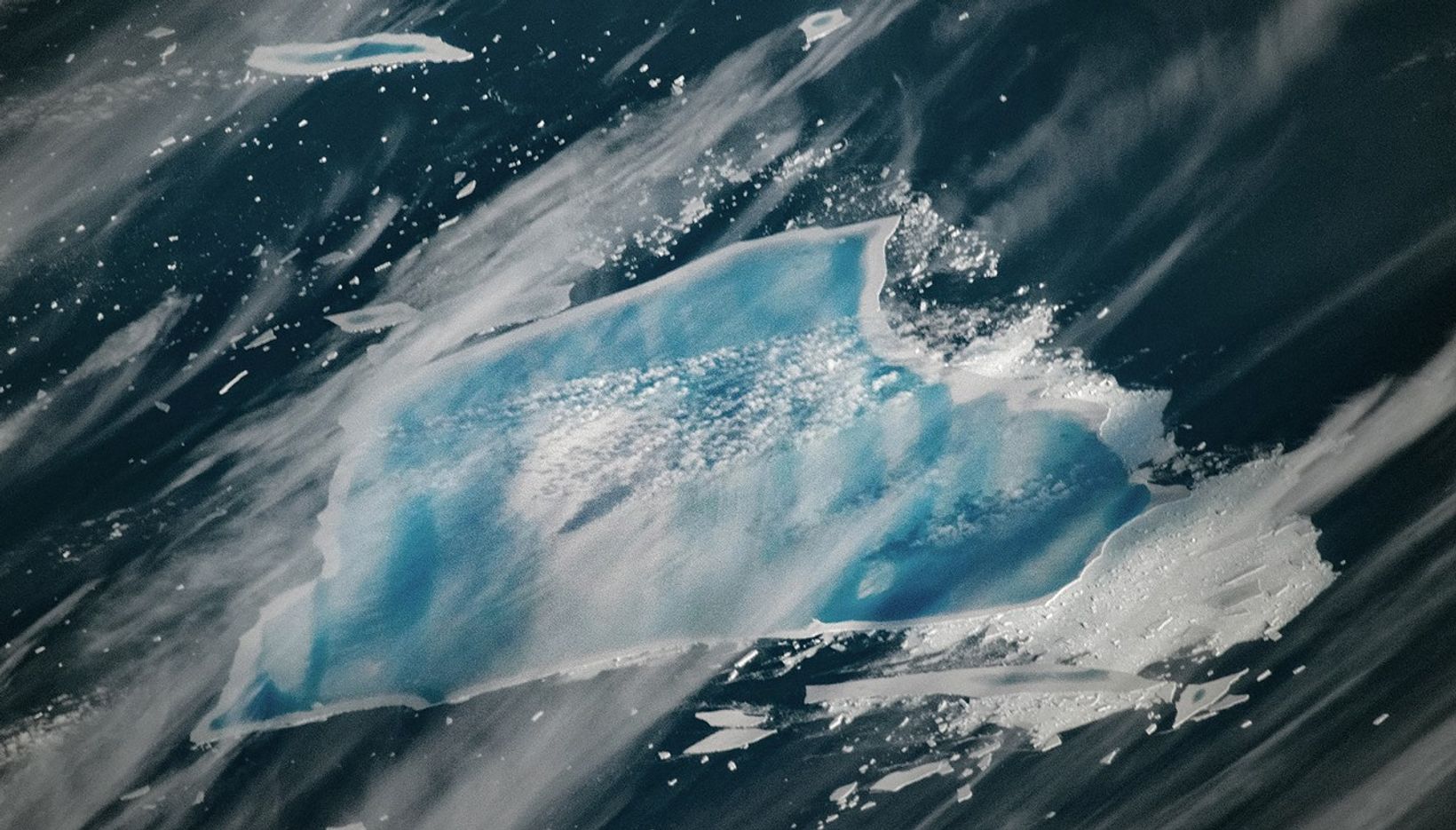

The more southerly blaze was spreading east on ridges between Lago Rivadavia, Lago Futalaufquen, and Lago Menéndez; the more northerly fire was burning on steep hillsides around Lago Epuyén. All of the lakes occupy U-shaped glacial troughs, valleys with unusually flat bases and steep sides carved by glacial and periglacial erosion. Satellite-based estimates from the Global Wildfire Information System indicate that fires charred more than 175 square kilometers (67 square miles) across Patagonia between January 5 and 8.

The ridges are blanketed with temperate Patagonian Andean forest, including sections of Valdivian rainforest, with rare stands of alerce (Fitzroya cupressoides). A type of cypress, these huge, slow-growing conifers are the second-longest-lived trees on Earth, with some surviving for more than 3,600 years. According to UNESCO documents, Los Alerces National Park protects 36 percent of Argentina’s alerce forests, including stands with the greatest genetic variability on the eastern slopes of the Andes. The park’s forests also contain exclusive genetic variants and the oldest individuals in the country.

News outlets and the national park reported challenging weather conditions for firefighters on the ground, who faced high temperatures, low humidity, and strong winds in recent days. Standardized Precipitation Index data from the National Integrated Drought Information System show that unusually dry conditions over the past several months have likely primed vegetation to burn. News outlets reported that at least 3,000 tourists had to be evacuated from a lake resort near Lago Epuyén.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Michala Garrison, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Adam Voiland.

References & Resources

- Argentina (2026) Parque Nacional Los Alerces. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- Buenos Aires Herald (2026, January 8) Wildfires in Patagonia: 3,000 tourists evacuated as flames consume Chubut forests. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- El Destape (2026, January 5) “Situación explosiva o extremadamente crítica”: alerta por posibles incendios en casi toda la Argentina en el verano. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- France24 (2026, January 7) 3,000 tourists evacuated as Argentine Patagonia battles wildfires. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- LM Neuquén (2026, January 8) Incendios forestales: los lugares habilitados para el turismo en la cordillera. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- NASA Earthdata (2026) Wildfires. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- Noticias Ambientales (2026, January 8) Alert for fires in Chubut: nearly 2000 hectares devastated, 3000 evacuated, and the fire doesn’t stop. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- ReliefWeb (2026, January 8) Argentina – Wildfires. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- UNESCO (2017) Los Alerces National Park. Accessed January 9, 2026.

You may also be interested in:

Stay up-to-date with the latest content from NASA as we explore the universe and discover more about our home planet.

The Bear Gulch fire spread through dense forest and filled skies with smoke in northwestern Washington state.

The fast-growing blaze charred more than 100,000 acres in the span of a week.

Far from large urban areas, Great Basin National Park offers unencumbered views of the night sky and opportunities to study…

The post Fire Threatens Rare Forests in Argentina appeared first on NASA Science.